This is what I’d tell you

Part of my disposition that lends itself to art-making is a mind for images, or rather, that memories to me are like quick photographs. I can’t remember where my keys are and I forget instructions as soon as they’re given but I can recall, almost perfectly, the way my father used to pluck the wishbones from the turrs he cooked on Sunday afternoon. He would leave the oven on long enough to hang the small bones on the rack where they baked and hardened. Then my sister and I would wrap our pinky fingers around the ends, close our eyes, and make a wish as we pried apart the bones until one of us was left with the longer, splintered end. We never cared about the act of wish-making. Instead, we cared for the ritual and how this seemed like a private thing, meant only for my sister and I.

I hadn’t thought about this in years. Then I saw Ann Manuel’s wishbones hanging on the gallery wall at Union House Arts and I was once again a child sitting at the dining room table, gripping a wishbone with my pinky.

Growing up in my house, my father was the cook. My mother preferred to be outside. She’d rather dig up a rosebush or shovel the driveway than make a Sunday dinner, though she was in charge of everything else related to our domestic lives. She did the laundry and she cleaned the house and she paid the bills and she did the grocery shopping. She was also often angry. She had a temper that seemed to come out of nowhere. As a child, this anger felt one-dimensional to me. I didn’t understand how it took shape or what its use was.

Now that I’m an adult woman living with an adult man, my mother’s anger suddenly makes sense. During the earlier parts of my relationship, while my partner and I were figuring out (i.e.: arguing about) the division of domestic labour, I would think of my mother. I’m an artist with no children, who works at home, able to do the laundry whenever I want, telling my boyfriend that if he doesn’t start to grasp the concept of unpaid domestic labour and clean up after himself, I will either a) lose my mind or b) leave him. Meanwhile, I wondered how my mother—who worked twelve hour shifts at the hospital on the long-term care unit where she cleaned and fed patients, came home to my father, my sister, and I and spent her free time scrubbing the toilet—managed to hold on to any semblance of sanity.

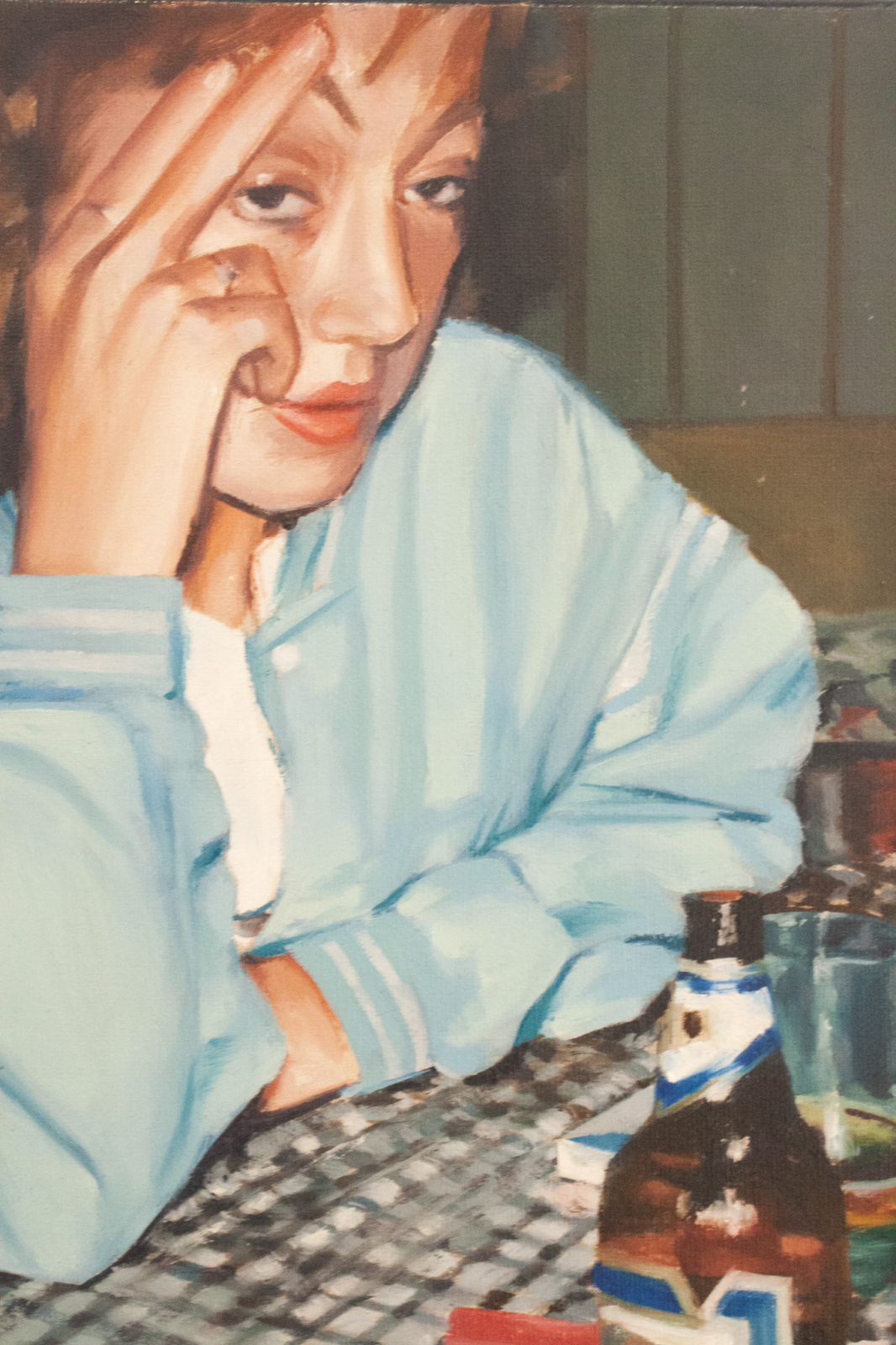

It’s worth noting that in the exhibition tell them from me, the works that more obviously hint at this womanly rage are mine. I’m drawn to depictions of womanhood where this anger is like a pot simmering in the background. One of my paintings included in the exhibition, The Cabin, is of my young mother looking annoyed while sitting in a dark room at a table with a beer bottle, a pack of Player’s Lights, and a hairbrush. In my mind, this painting speaks to the way I’ve always been aware that my mother had a secret life she longed for. She was a woman who often seemed unsatisfied with the life she’d chosen for herself. Womanhood, and even motherhood, has always been modelled to me this way, with a touch of dissatisfaction and anger. It’s not shocking to discover that I am a woman who yells, and it seems inevitable that should I become a mother, I will be the kind who curses and screams with one breath and loves with the next.

What tell them from me exhibited so tenderly was all that is encompassed between the screaming and the loving, like the secret longing, the labour, the wisdom and care. Each of the pieces transitioned me to a moment within the sometimes fraught relationship I have with my mother, yet the show held all the reverence I have for her and the long matriarchal line I’m part of.

In the back room of the exhibition, a pair of jeans were printed on cheesecloth and strung across the gallery wall, one of Ann Manuel’s works, and I thought: I want to become a woman who hangs clothes, like my mother is and like her mother was. So this fall, I hung a clothesline, and though I live in a city where it rains so often that it rarely gets used, it feels important that it’s there, that I can see it over the top of my computer where I write each morning, and I get the feeling like I’m part of something, a lineage of womanhood.

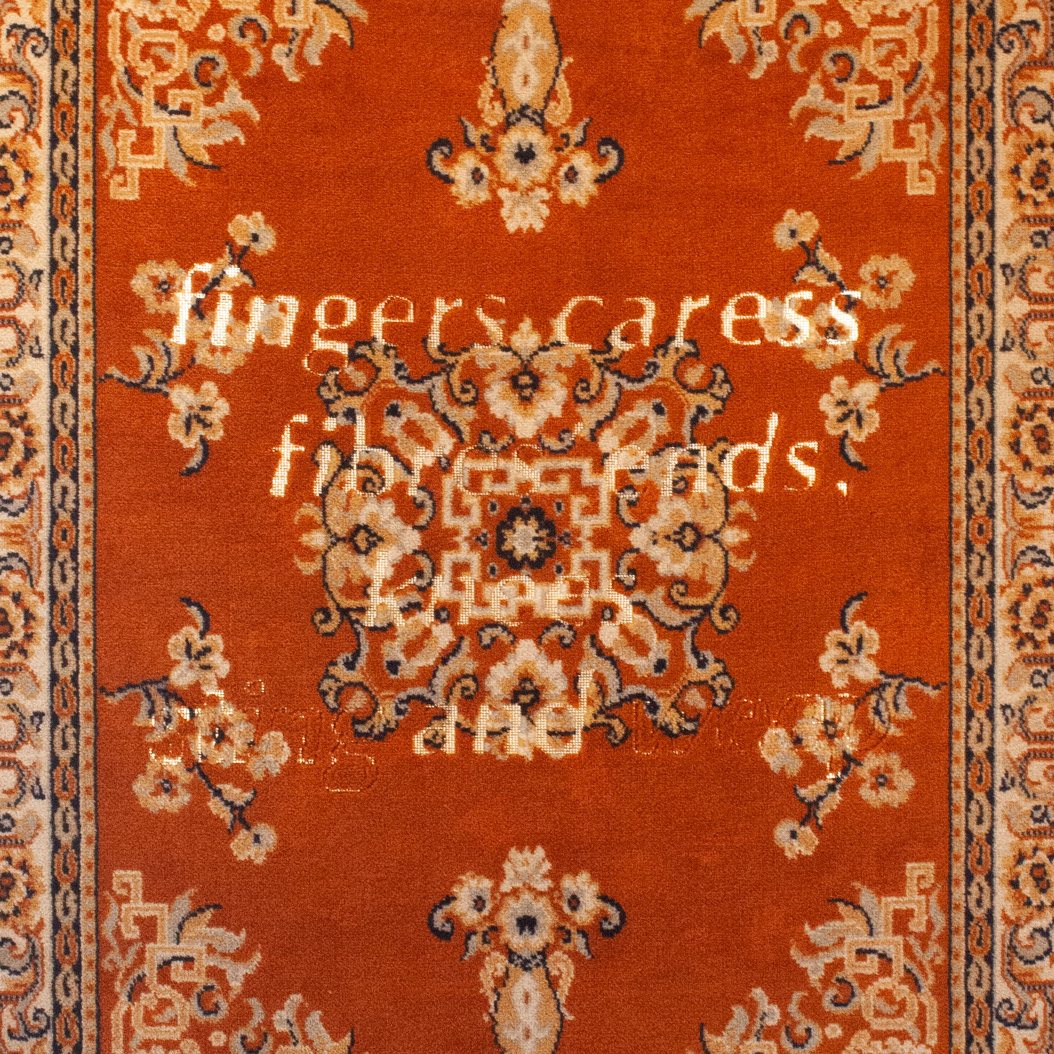

There are so many parts of my mother that I wish to emulate, like how hard she works and the way she laughs. Yet, ever-present in myself are the parts of her that I wish I could resist, like her temper and her tendency toward sadness. Being with the pieces in tell them from me was a reminder of this, the way Emily Hayes’ decadent rug, plucked of its threads to read fingers caress fibres’ ends, knees sting and weep, spoke to me about the sadness threaded through my mother’s care. The way she’d disappear into a depressive episode, then reappear at the sewing machine upstairs or the garden where she planted peonies and hostas.

An image of her I’ll always keep in my mind is of her standing in rubber boots with her elbow braced on top of a shovel on the day I got suspended from school and she made me work in the garden and swore she wouldn’t tell my father. This came to me, as I stood in front of Ashley Hemmings’ hooked rug. Hanging on the wall was a life-sized Nan, standing in bright grass, smiling with her hands crossed, full of patience and care. Distance makes the heart grow fonder, it read. Bullshit makes the grass grow longer. There, amongst Ashley’s yarn, wool, and burlap, was the woman my mother would become, if I were to let her.

My parents have no grandchildren. Whether my mother becomes a grandmother is solely in my hands, a responsibility we don’t speak too much about, yet I feel the pressure of giving this to her, of saving her from some sort of end-of-life, grandchild-less disappointment, to have a child that will carry on her quirks and charm, and love her in the faultless way that only a grandchild can. I loved my grandmother in a way that feels similar to how Ashley Hemmings must love theirs and it’s a love I want my mother to know.

Woven throughout the exhibition were Alana Morouney’s felted hands and knots, holding everything together. And isn’t this always the case? The women, whose work is so often unseen and unrecognized, holding the fabrics of our families and lives together, yet they’re often so close to fraying themselves?

Being with the works in tell them from me, so lovingly and tenderly curated, felt like being with a sentiment impossible to express. How do we tell our mothers and grandmothers that we recognize everything they’ve done and all it took from them? How could we possibly ever explain?

tell them from me exhibited this place where language cannot account. Here is everything we’d tell you, the exhibition said. If only there were words enough.

–Sabrina Pinksen, 2024

Thank you to ArtsNL and Canada Council for the Arts for funding our 2024-2025 exhibition season.